The way we make science is simultaneously saving and dooming us

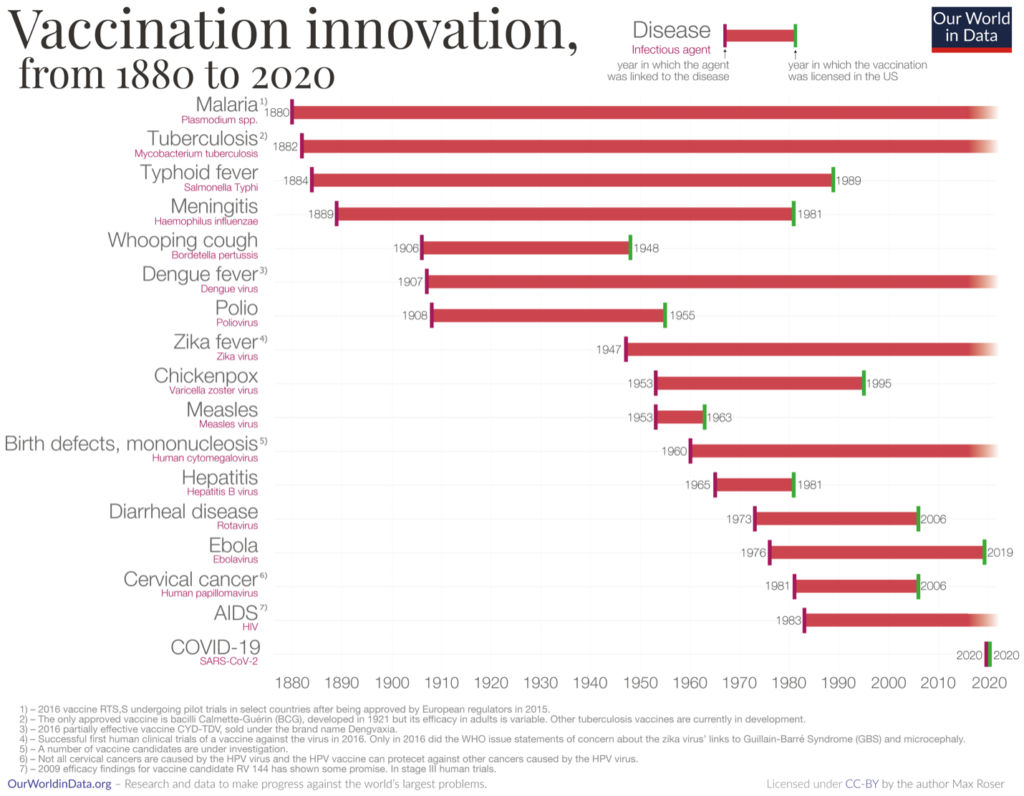

Roughly eighteen months after COVID-19 vaccines first made it to market, it’s easy to forget how unlikely it is that they were developed at all. When the COVID-19 pandemic began, no vaccine had been brought to market in under 10 years, and most had taken two-plus decades to develop. More daunting, by March 2020, only two effective vaccines—for human papillomavirus (which took 25 years) and rotavirus (which took 33 years) had been brought to market in the past four decades.

With all that in mind, it’s worth applauding the insane sprint that brought us a vaccine in the middle of a pandemic, something that had never been done before, nor even attempted, given how long the road to a vaccine was and how quickly pandemics spread. That means, of course, celebrating the efforts of Pifzer, Moderna, Johnson & Johnson, AstraZeneca, and other pharmaceutical companies—and that’s not something that most people feel comfortable doing. After all, pharmaceutical companies are in the business of maximizing profits at the expense of people’s pain. Right? Well, yeah. And COVID-19 has illustrated why that profit motive isn’t just morally unpleasant but actively undermining humanity’s capacity to protect itself from pandemics.

Future threats aren’t good business

In May 2020, when I was in the early days of research for The Invisible Siege: The Rise of Coronaviruses and the Search for a Cure (have you heard it’s now available and that you should buy a copy?), I spoke with Nat Moorman, a virologist at the University of North Carolina. Moorman had spent his career studying human cytomegalovirus but had like so many in his field been dragged into coronavirus research as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded. It was a heady time, with the vaccine race barely out of the gate and the world following each development with baited breath. “What would you have paid me for a COVID-19 vaccine a year ago,” Moorman mused to me at the time, before answering his own question. “Nothing.” He was right, of course: before the pandemic, there was no financial incentive to develop a vaccine or therapeutics that could protect the human race from viruses that didn’t yet exist, despite the fact that more pandemic-ready pathogens have emerged in the past twenty years compared to the entirety of the 20th century and that everyone knew another one was sooner or later going to appear.

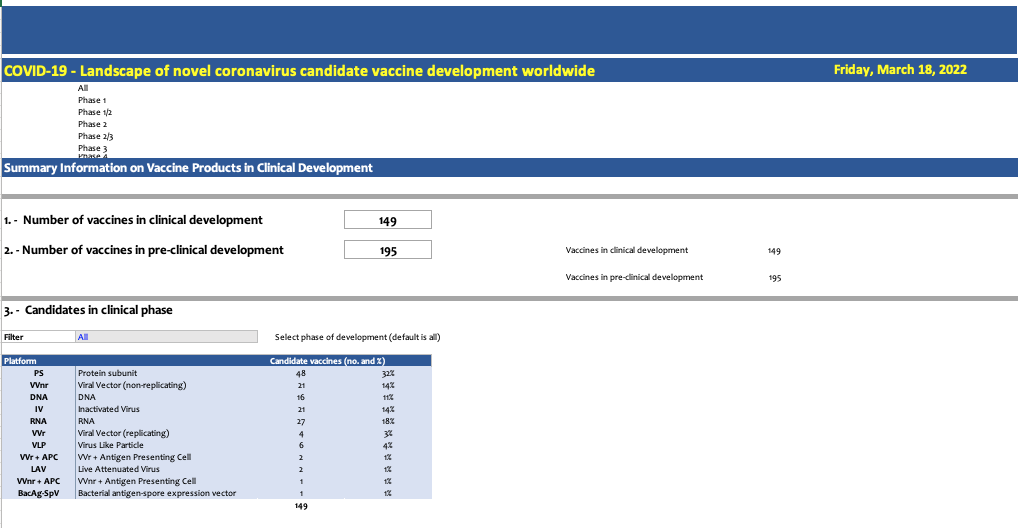

That financial disincentive to plan for the future is only half of the story. The other half is that when a health crisis like COVID-19 hits, the market incentives to respond can reach absurd lengths. Case in point: despite the fact that there are at least five highly-effective COVID-19 vaccines currently on the market, there are also as of today—wait for it—about three hundred and fifty COVID-19 vaccines in development.

Let that sink in. The market already has more COVID-19 vaccine options than we need (though, as I pointed out in a previous newsletter, far from enough doses for people living in lower-income settings). And yet, three hundred and fifty pharmaceutical companies, biotechs, and research labs around the world think it makes good financial sense to develop even more. The worst part is, they’re probably right: the market rewards scientific discoveries that fit into the current paradigm. That’s because even if a new COVID vaccine is useless, developing one has become a benchmark for scientific success that signals to investors that your group is worth pouring dollars into.

This is why a small but growing contingent of scientists and legal experts are calling for an open science approach to discovery. I wrote about this in my Globe & Mail op-ed, but briefly what open science means is that discoveries aren’t patented. Just as important, though, is that other proprietary aspects of producing cures are shared. This includes, for example, the recipe for the lipid bubble that Pfizer and Moderna use to transport their vaccines into human cells, the techniques that vaccine manufacturing plants use to produce doses, and the vaccine storage process used to ensure that doses aren’t destroyed in transit. The point of opening up this knowledge is to remove the financial roadblocks that have stalled out the search for life-saving discoveries that can’t promise to produce revenue.

This includes cures for diseases like malaria and Dengue fever, which kill hundreds of thousands of people in low-income countries each year. But what should concern us all is that it has also fully stamped out efforts to develop vaccines to protect us against one of the twenty-six viral families that haven’t yet spawned pandemic-causing pathogens but have the potential to infect humans. It’s a collective action problem: everyone knows that it’s just a matter of time until that happens, and nobody wants another pandemic. But in our current system of for-profit discovery? None of that matters.

It’s a sad state of affairs, and there are at least some signs that the approach to discovery might be shifting. Until it does, at least we can look forward to the arrival of hundreds more COVID-19 vaccines into the marketplace.

Happy shopping.

Meanwhile, in Dan Werb news…

It’s been a fun few weeks since the launch of The Invisible Siege and I’m so happy it’s out in the world. Lots has been going on but some highlights are (in no particular order):

I was so thrilled to launch the book (virtually) at Warwick’s in San Diego, a beautiful independent bookstore that is also the U.S.’s oldest family-owned bookstore in the country, which is no small feat. If you missed the launch, which included a great discussion with Davey Smith (head of infectious diseases at UC San Diego, and a key scientists profiled in The Invisible Siege), you can watch it here.

The very august Walrus Magazine published an excerpt from The Invisible Siege that covers two points in humanity history when new coronaviruses emerged to threaten our species. What happened next? Read on…

Last week I also published an op-ed in TIME under the headline “To End COVID, We Have to Admit That We’ve Failed”. If you’ve reading these newsletters you know that I’m fascinated by how scientific failures become sturdy foundations for life-saving advances. Check it out. Hint: it’s a good news story.

Thanks for reading. If you haven’t yet, please pick up your copy of The Invisible Siege: The Rise of Coronaviruses and the Search for a Cure. I’m not generally filled with confidence about the creations I send out into the world, but this one’s special.

And if you are reading the book and liking it, please tell people about it, and—if you’d be so kind—consider writing a review on Amazon or Goodreads. You have no idea how much that kind of thing helps get the word out.

As always, if you enjoyed this newsletter and haven’t yet, please consider subscribing and telling people in your life that you think would enjoy it.

See you next time.