How our inability to end one pandemic is saving us from another

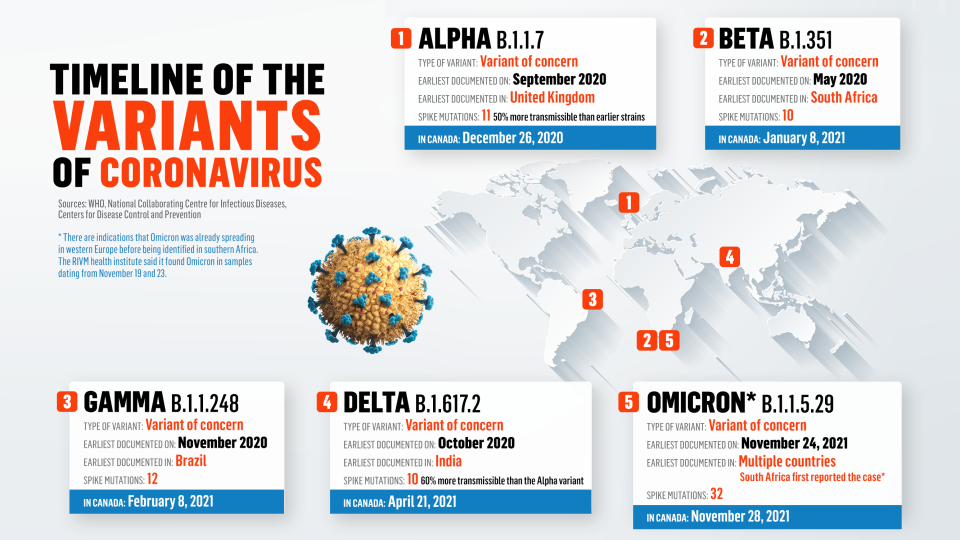

In my last newsletter, I covered some of the issues around chasing the end of the pandemic with vaccines. Basically, it boils down to what Ralph Baric—the world’s greatest coronavirus researcher—describes as an inevitable flood of SARS-CoV-2 variants that will elude vaccines faster than we can produce and distribute new ones. Those variants emerge in places where the virus is replicating plentifully (the cool scientific term is ‘transmission cycles’), and they will continue to do so until there are no more pockets of susceptible hosts (read: non-immune humans) to infect and mutate within. Phew. If you want to read about Baric’s forty-year journey from outsider coronavirologist to one of the most consequential scientists alive, it’s all in my upcoming book The Invisible Siege: The Rise of Coronaviruses and the Search for a Cure.

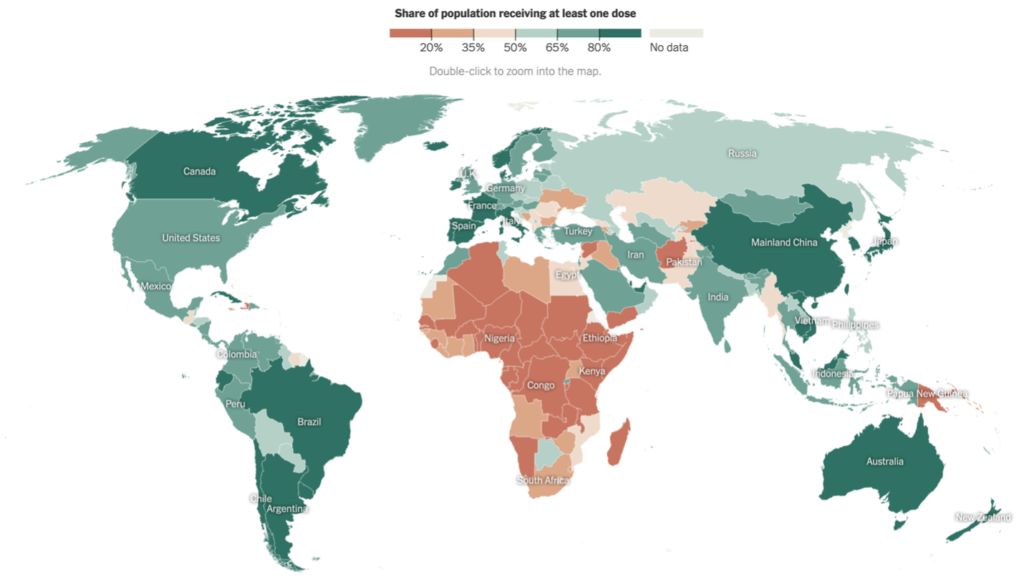

That grim scenario wouldn’t hold, though, if the whole world got vaccinated. But between the pitifully low lack of access to vaccines in low- and middle-income countries and the hyped up anti-vax movement, we’re not going to get close to global herd immunity, which is what’s needed to stop the pandemic. So. What are the options?

Hope. And no, that’s not a joke.

Well, this is where there is, actually some good news. And it’s not just about this pandemic: it’s good news about whatever future coronavirus pathogen next threatens humanity (and yes, there will undoubtedly be more). And like so many scientific successes, this one is rooted in abject failure.

Decades after its discovery, HIV remains one of the world’s most dangerous viruses. But, as we’ve all heard many times, it has been transformed from a killer into a chronic condition. What’s remarkable, though, is that this was all done without a vaccine. The HIV virus is so elusive (it turns the body’s own immune cells against itself) and so slippery (it mutates at a clip that makes SARS-CoV-2 look like its standing still) that every attempt to create a vaccine—and there have been many over the past forty years—have failed. And still, humanity somehow found a way to control the spread of HIV.

That we were able to do so in the absence of a vaccine is one of modern science’s greatest achievements. So how did it happen? The trick was, basically, to assume that the virus was going to burrow its way into human hosts, and that the focus should be on disrupting it once it did. In practical terms, that meant forgetting about vaccines and focusing on antiviral treatments that could stop the virus replicating. It’s a bit like trying to stop the snow from falling (and forgive the simile; I’m writing this from Toronto, where there’s been record snowfall), which is something nature decides, not us. That doesn’t mean, though, that we have to throw ourselves at the mercy of the elements. We can equip ourselves with multiple tools—a warm jacket, waterproof boots, and a shovel—to make sure that when the snow hits, we stay warm and protected.

So it goes with antivirals. They won’t help your immune system kill viruses before they find a reservoir inside your body, but they will protect us from the worst of an infection by hindering a virus’s capacity to replicate. In the case of HIV, a combination of antiviral medications (known collectively as highly active antiretroviral therapy) has become so effective that HIV-positive people who take them can have so little virus in their bloodstream that it can no longer be detected, let alone make them sick. It’s an incredible feat—the control of a deadly pandemic-level pathogen without a vaccine—but that’s only the beginning. Because HIV medications reduce the amount of virus in a person’s bloodstream to undetectable levels, they also make it essentially impossible for someone infected with HIV and on treatment to infect other people: there just simply isn’t enough virus in their bloodstream to be a threat. This technique—using medications designed to control AIDS-related illness to stop the spread of a vaccine-dodging pathogen—is known as Treatment as Prevention, and it’s revolutionized the way we think about elusive pathogens.

Antivirals got lost in the COVID vaccine frenzy, even though they might just be our way out…

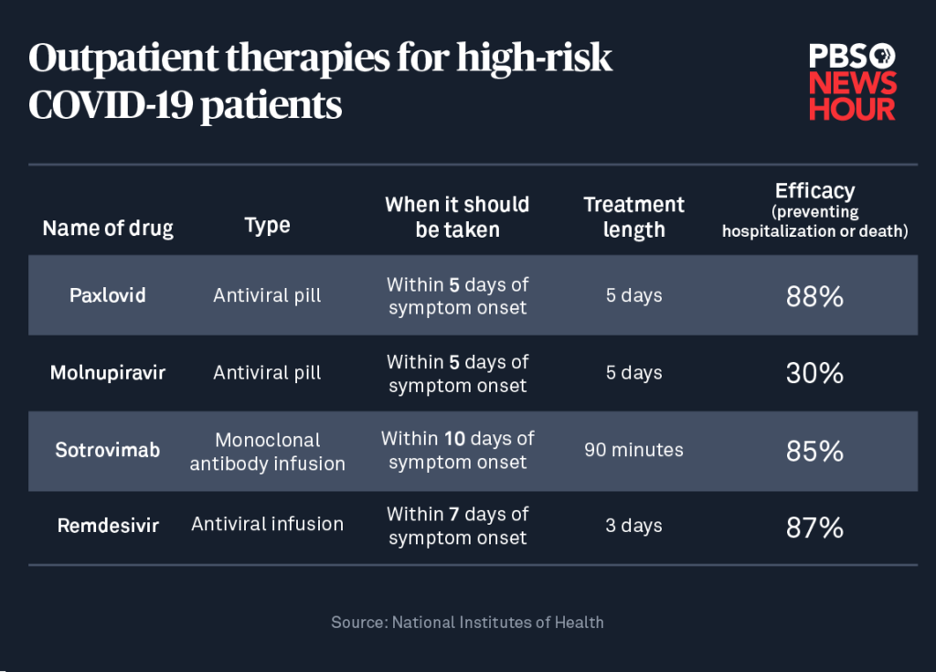

There are clear lessons here for the future of COVID-19, and for once they’re uniformly positive. We now have multiple approved antiviral medications—Pfizer’s Paxlovid, Molnupiravir, and Remdesivir—that disrupt different stages of SARS-CoV-2 replication. What’s great about these is that they all target parts of the virus that aren’t prone to mutating, unlike the spike protein, which is the target of all current vaccines and which mutates at roughly three times the rate of rest of the virus.

That means that, even if the vaccines fail against future variants, antiviral medications almost certainly won’t. Multiple studies show that COVID-19 antivirals reduce moderate and severe illness by up to 90%, and that they could even protect hospitalized people from needing a ventilator. There’s even good evidence that they could even protect against infection if taken prior to exposure to virus; say, if someone in your family or social network tested positive. And that starts moving things into the realm of Treatment as Prevention: COVID-19 treatments that can stop people from getting sick while also stopping the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus itself.

This is ‘end of the pandemic’ stuff, for two reasons. First, because, as I mentioned, the COVID-19 antivirals target parts of the virus that don’t mutate rapidly, so they’ll likely remain effective over time. Second, because these treatments are cheap and easy to distribute, especially compared to the COVID-19 vaccines, which means that Treatment as Prevention campaigns could be deployed to places around the world where outbreaks are occurring and could stop them in their tracks. It’s an unbelievably effective public health approach, and it brings me unadulterated hope for the future.

I’ll end on one last piece of good news. The parts of the virus that these antiviral medications target haven’t only remained stable across all the SARS-CoV-2 variants. They’re also present in every single coronavirus that has ever been discovered. That means that, no matter what coronavirus pathogen shows up next—and SARS, MERS, and SARS-CoV-2 makes it three in thirty years—we can have a lot of confidence that the antivirals that work against COVID-19 will protect us from the next abomination nature sends our way. Does that spell the end of coronavirus pandemics? It just might.

*

Meanwhile, in Dan Werb News:

We are one (!) month away from the publication of The Invisible Siege: The Rise of Coronaviruses and the Search for a Cure. There have been some more really positive reviews filtering up, including in Library Journal (paywalled, but thank you librarians, anyway) and from some goodhearted early readers, which you can see on Goodreads. I’m getting pretty amped to have this book out in the world. As always, you can pre-order it here.

*

Thanks for reading. You can find me at my website and on Twitter. If you want to go deep on my science, check out my one true love: Pubmed. If you haven’t yet signed up for this newsletter, or know someone who would like it, go ahead and do it here.