Newsletter / Science / Epidemics / Writing / Non-Fiction

It’s never too late to bend the arc

Also: PUB DAY!!!!

One of the more curious side effects of the pandemic has been on our relationship to time. In conversations with friends, I’ve often heard the same thing: a pandemic day feels like an entirely different amount of time compared to pre-pandemic days. Hours have stretched themselves to absurd lengths, days have become seasons, months years, and the years themselves; well, best not to even think about them, lengthened as they’ve been into stifled lives, accompanied by pulsing boredom and anxiety. As restrictions get lifted in many countries, it’s as if we have to re-learn what a day—a real day, out in the world—feels like again. It’s euphoric and scary and feels, maybe more than anything, like a gift from the universe.

But that experience of pandemic time isn’t the only reason it’s been on my mind. Early in the writing of The Invisible Siege: The Rise of Coronaviruses and the Search for a Cure (did I mention it is out today and you can order it here?), when most of my conversations, it seemed, were with virologists, I was struck by how limited my idea of time really was. More than that, I realized that there were two universes of time that I would have to contend with in the book: human time and viral time. Human time is, by this point, instinctive for us: we’ve trained our internal clocks to the rising and setting sun, and even have a vague awareness of how long a decade or century might be. But viral time…that’s something else entirely.

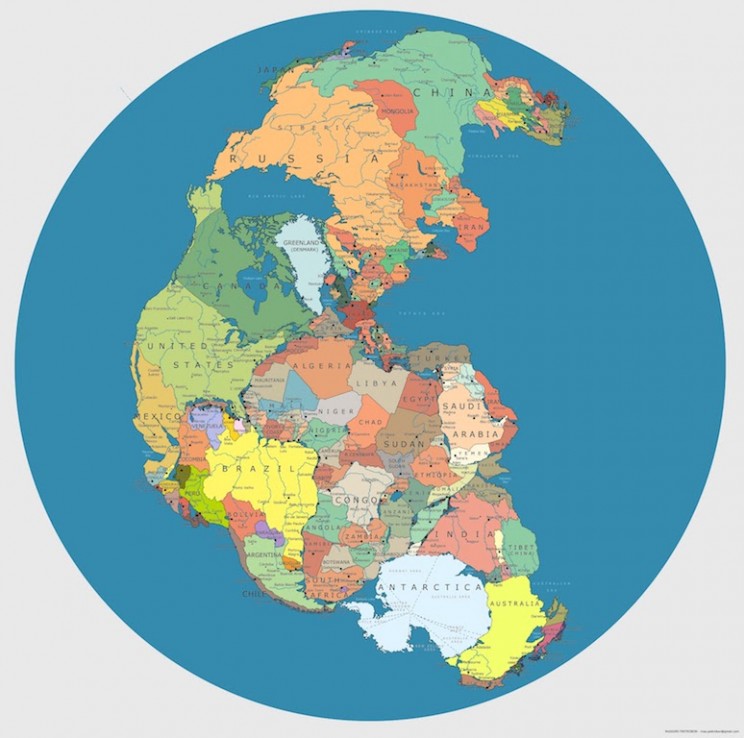

Coronaviruses, it turns out, replicate every three minutes, an absurdly short cycle that compresses what we think of life down to the blink of an eye. But trying to understand a virus through the strange dance of a single virion is like trying to understand what makes a beach by looking at a single grain of sand: everything important is obscured. Viral time isn’t just about a three-minute replication cycle. It’s about the long churning evolution, spurred on by mutations that accrue in each new virion, that happens over hundreds, thousands, and millions of years. And that’s what we’ve been contending with over this entire pandemic: a virus that represents, by some estimates, the product of 300 million years of evolution.

Yes; you read that right. And for those of you up on your human evolution, you’ll know that homo sapiens, our beloved species, only emerged 300,000 years ago. Coronaviruses didn’t arise to meddle with humanity. Our species was born into a coronavirus world. This family of viruses, the Coronaviridae, had been preying on humanity’s ancestors for hundreds of millions of years before our species evolved. No wonder, then, that coronaviruses are so expertly attuned to our biology: they had time—eons of viral time—to practice. But if there’s anything that this pandemic has taught us, it’s that our species has been able to make up the coronavirus’s running head start to the point that the end of this battle is in sight.

Care to spend some of your human time with a book?

There’s another reason I’ve been thinking so much about time, one that hits much closer to home. If you’ve been reading these newsletters, you probably know that today is publication day for The Invisible Siege: The Rise of Coronaviruses and the Search for a Cure. And if you’ve been enjoying them, please click on the link above and get yourself a copy of the book. Reviewers have so far described it as “page-turning,” (Publishers Weekly) and replete with “vivid storytelling” (David George Haskell, author of The Forest Unseen). Richard Preston, one of my literary heroes and the author of bestselling book The Hot Zone wrote, “I learned so much that I didn’t know before—above all, I met the subtle warriors of the laboratory who are working to save all of us from the horror of new pandemics.” That was pretty nice.

If you like reading and you’re interested in an optimistic counter-narrative about what went right before and during the pandemic (and you’ve come this far, so evidently you do), then please consider buying a copy of the book.

If you want to help with getting the word out, the absolute best things you can do is order the book, post about it online, and when you read it and love it, write a review on Amazon, Goodreads, or your personal diary (I’ll know). It’s no secret that selling books is hard. So let me be the first to say: thank you!

Meanwhile, in Dan Werb news…

(Virtual) book launch!!!! Wednesday March 9th @ 4pm PST / 7pm EST!

I’m so thrilled to be launching the book at Warwick’s, a gem of a bookstore in San Diego/La Jolla. I had an amazing time with the City of Omens launch in 2019 and looking forward to returning. I’m also thrilled to have Davey Smith joining me. Davey is the head of Infectious Diseases at the University of California San Diego, an Operation Warp Speed scientist who tangled with Trump, and one of the main characters profiled in The Invisible Siege.

RSVP at this link – I can’t wait to see you there! https://www.warwicks.com/event/werb-2022

Q&A about The Invisible Siege

I did a short Q&A about The Invisible Siege that you can check out here; it covers some of the themes explored in the book, including why I dedicated it to “those who were not saved”.

Op-Ed on Open Science

Last weekend, I also published an op-ed in the Globe & Mail about open science, a model of discovery that seeks to create cures based on global need, rather than on the profit motive. The op-ed delves into some of the missed opportunities for open science before the pandemic, and why it’s more needed now than ever.

Miscellany

There’s also going to be an excerpt of the book going live later today – check my twitter feed for updates.

And, as always, if you enjoyed this newsletter and haven’t yet, please consider subscribing and telling people in your life that you think would enjoy it.

See you next time, when I’ll cover the lessons—right and wrong—that we’ve learned through this pandemic, and how we can develop a foundation for scientific discovery that anticipates that last great mystery: the future.